What I like to do best in this blog is tell stories—preferably witty and arch ones wherein I prevail in battle against the forces of romantic villainy and chaos (or, if necessary, turn a defeat into a clever little anecdote which represents me in a sympathetic and nobly-heroic light). But in recent weeks, I’ve had no stories to tell because my one-woman Romantic Justice League has been languishing in idleness. I’ve been doing all sorts of Important Things; I’ve been Productive; I’ve upgraded my cable so I can watch Game of Thrones and True Blood which provide all manner of stimulation and provocation—but I haven’t had a date promising or maddening enough to write about in forever.

If I were a field of hay, I guess this would be my season to lie fallow. I seem to be in a mode that my friends refer to as “brain-on-a-stick”: lots of good mental and emotional work going on on top, complete indifference to the non-goings-on from the neck down. My boss and my résumé appreciate this state of affairs greatly. My own response is a little bit more mixed.

My low point came a couple of weeks ago, as I was in the throes of finishing a huge writing project—lexically huge at 13,000 words; psychically huge as I’d come to invest the piece with every bit of my professional and personal identity. I was intellectually distracted, short-tempered, harried. I was having hypochondriacal fits about mysterious goings-on with my teeth, my toe, my tongue (over-zealous tongue-scraping)—which was stupidly ironic as I was writing about psychosomatic illness. I wasn’t too tired, but only because I was generously sedating myself every night. I felt too bad to make it to salsa or the gym. I had a terrible cold. And my hair was kind of falling out, because—fun, new age-related change—I molt when I’m stressed. The writing was coming to a crisis: was I going to get this thing done, and finally be free of it after 3 years of research? was the world (well, at least the journal editor and two peer reviewers) going to welcome it? or was it the rantings of a complete madwoman? I really had no idea, but I just carried on, in a frenzy of miserable work.

I did a lot of this work in bed. They say that for good sleep hygiene you should only use your bed for two things, but since I was only getting one of them, artificially (um, still talking about sleep), and I don’t have a lot of surface area elsewhere in my very small apartment, the bed was drafted into service as office. So it was that on one recent Tuesday, around 8 am, you would have found me, en deshabille, hair tangled, no makeup, surrounded by laptop and drafts and notes scrawled on scraps of paper; my sinuses were draining energetically; my cough was, from a medical standpoint, healthily loose and productive—which means I was barking like a consumptive dog; I was slopping coffee as I pulled it distractedly from the night stand; there was ink on the pillow cases, molted hair and sriracha on the sheets, used tissues on the floor.

Coming back to the bed from the kitchen—forced to stop by a fit of coughing which demanded follow-up nose blowing, which resulted in more spilled coffee—I thought: huh, this is kind of a low point. (It wasn’t quite as bad as Tracy Emin’s installation, but on its way). What made it especially low was that I was aware of this disreputable disarray and, simultaneously, completely indifferent to it. Consumed by the drive to make my deadline and my own physical misery, part of me was horrified that I wasn’t more actively horrified by the squalor—and part of me was actually perversely gratified: See?? (I thought, in the editorial plural) We can be focused, unrelentingly productive, and triumphant over adversity after all!

In the midst of this episode, I’d get updates from one dating site or another—and never mind the truly unsettling number of unsuitable suitors—I’d catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror, disheveled and haunted, and think, now is not the time.

Which was a bit odd, because I obsess about dating a lot (Guys, don’t flatter yourselves too much. For contextL: I obsess about everything a lot; I’ve spent the past weekend alternately worried about such pressing business as my toe, my work, my weight, my hair, and whether or not I’m entitled to a new suitcase). To have no psychic energy to spare for hypothetical men was unusual, a rare break in the obsessive, self-absorbed clouds that usually shadow my mental landscape.

And then I realized, with a start: I’ve become the Lady of Shalott.

Everyone knows the story, from Tennyson’s narrative poem…or I’ll just give you the highlights here: A few miles from Camelot, a Lady lives alone in a tower. She spends her days absorbed in her weaving, and she can only look at the world as it’s reflected in a great mirror. She lives under a curse—we never learn whose, or the reason for it—and is forbidden to look directly at the world, or be in it at all. So she sits, and weaves, and looks at reflections of the world outside her tower: “I am half-sick of shadows, said the Lady of Shalott.”

Until one bright day, she sees something gleaming in the mirror—a knight, on his way to Camelot. And it’s not just any knight—it’s Lancelot, with gleaming armor, feathers on his helmet, noble carriage, coal-black curls. The man is, as Guinevere and Arthur would both agree, fatally perfect.

Overcome by beauty—of the whole world beyond the window, and, specifically, of this vision of masculine perfection—the Lady can’t help herself:

She left the web, she left the loom,

She made three paces thro’ the room,

She saw the water-lily bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look’d down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

“The curse is come upon me,” cried

The Lady of Shalott.

And that’s it for her. She leaves the tower, goes to the river, gets in a little boat, and starts to drift toward Camelot. By the time she gets there, she’s dead (that would be the curse). As her lifeless body floats past the stunned courtiers, Lancelot sees her and says, with who-knows-what intention: “She has a lovely face;/God in his mercy lend her grace,/The Lady of Shalott.”

See, the moral is you should stick to your weaving, and be content with looking at shadows of the world. Distractions—particularly pretty knights who couldn’t care less about you, and your mirrors, and curses—are nothing but trouble.

(Or the Lady’s curse is a metaphor for artistic obsession, or sexual repression. Or it just means that there’s safety in obscurity, and great risk if you leave obscurity behind).

When Tennyson’s poem popped into my imagination, I wasn’t really thinking of how the poem ended, more how it started—doomed to confinement in a tower, allowed nothing but work and fleeting glimpses of the outside world….

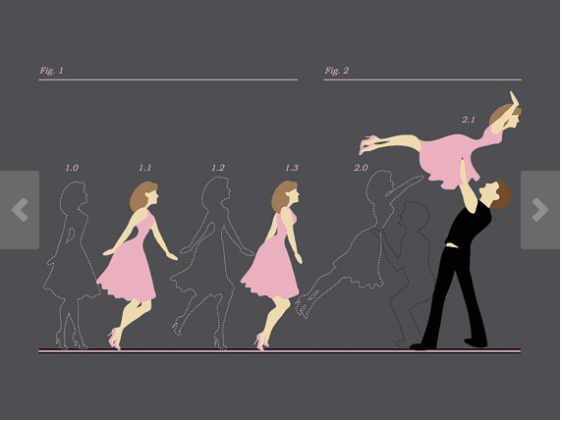

Then I thought: Oh, for heaven’s sakes! All of that Romantic suffering is well and good for Anne of Green Gables, or for 16-year-old Goth Me, but Current Me has too much to do to wallow in images of doom and curses. So what if I had a deadline, and a cold; so what if certain portions of my personal life were lying fallow; so what if I was feeling very brain-on-a-stick-y…? Those were all temporary conditions. I got the work done; my sinuses recovered; I went back to dance class and salsa night.

Unlike Tennyson’s Lady, I’m not actually living under a curse. If I’m occasionally confined in a tower, that’s because I just have to get some work done without distractions; and while I’ve been distracted by my share of would-be Lancelots, I’ve yet to encounter a knight so glitteringly compelling that he could drain all the life and will out of me in one fell swoop.

I mean, seriously.

If the only available identities are doomed pre-Raphaelite heroine, and doom-free, fallow brain-on-a-stick, I’ll take the latter (at least, as a temporary proposition), and get on with things.